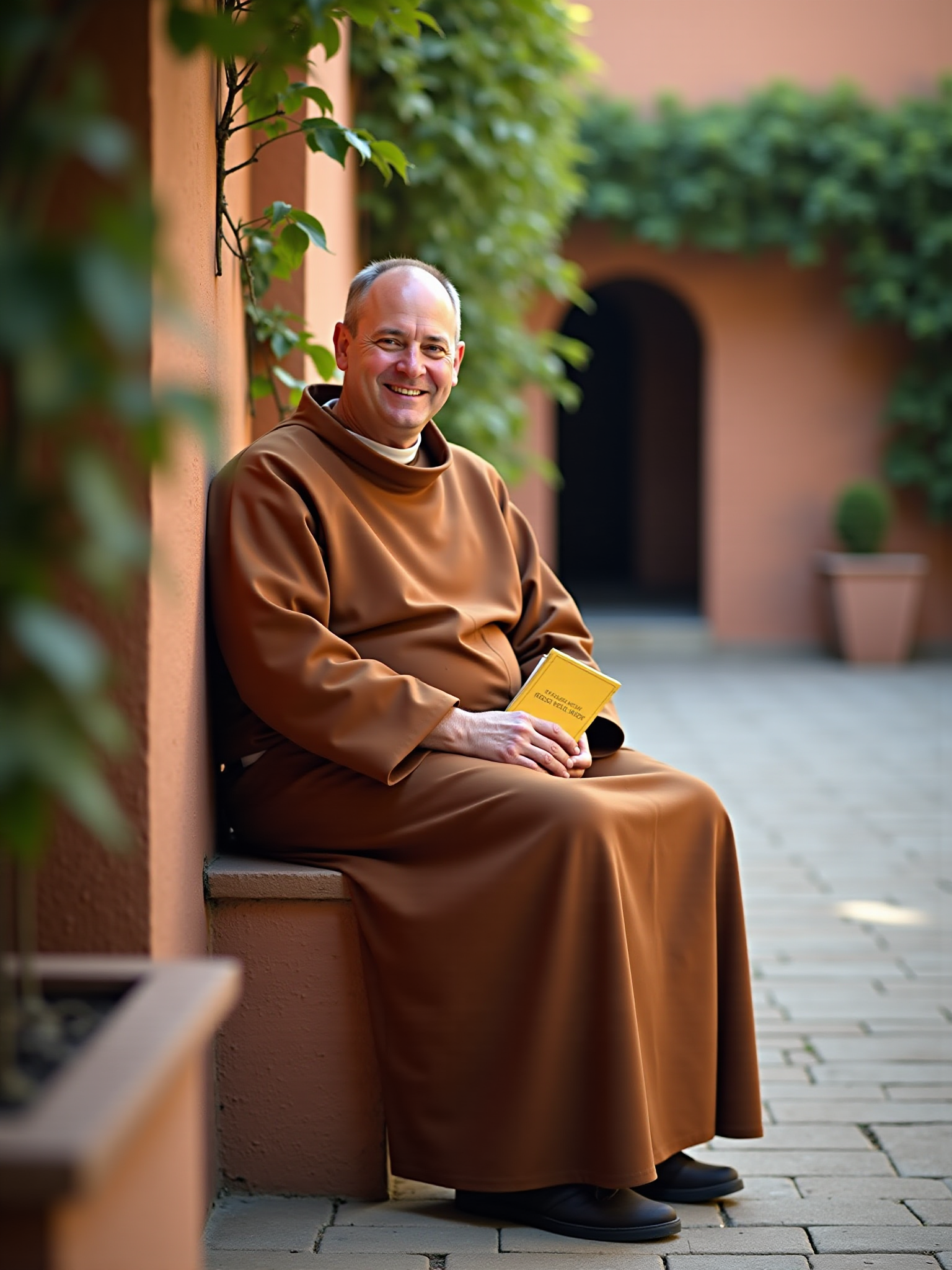

Ask Friar Robert

.jpg)

About Life

and Death

&

Everything

in between.

Welcome to Ask Friar Robert, where faith meets technology to provide a platform for folks to engage and learn. Dive into a world of spiritual growth, interactive discussions, and enriching content. Or just vent and get something off your chest.

I don't claim to have all the answers, but I'm a good listener.

Friar Robert: Why Do You Believe in God?

I'm a paragraph. Click here to add your own text and edit me. It's easy.

That is a very good question. The short answer is that since time immemorial, people have had experiences of something greater than themselves. For the longer answer, permit me to tell a story.

The Story of Michael

I was a young priest, not yet five years ordained and in high demand as a preacher. I had finished my dissertation, written a couple of books, and had my own radio and TV shows as well as a syndicated column. I thought of myself as hot stuff and bought myself a sports car to fit my image. That was all to change one cool, damp morning in November, 1986. The bishop of a local diocese had invited me to preach the annual Priests’ Retreat.

I’d been on the circuit for a while by then and had a collection of reliable talks that were sure to keep the lads listening. As I pulled my Grand Prix onto the interstate, I was running over the usual talks in my head. By the time I arrived, I had thirteen forty-five-minute talks picked out, complete with stories and laugh lines and pregnant pauses. This was going to be a well-rehearsed, professional performance.

The first days went as planned. Lots of head nods and laughs and applause lines. I could have done it all in my sleep.

Then came Friday morning, the last scheduled talk. On cue, I rose from my chair and strode to the podium with practiced flair. Over the course of the next forty-three minutes, I told the heartbreaking story of a young priest who had contracted AIDs back when AIDs was a death sentence.

Michael first suspected he had AIDs about six months prior, when lesions began to appear. When he finally went to be tested, he went into a depression that lasted for weeks. Still, he confided in no one because that’s what you did back then. Not only doctors and nurses avoided caring for AIDs patients; many members of the clergy knew neither what to think nor what to do. Michael had every right to expect that his confreres’ response would be no different. Once he picked up the phone and heard his bishop’s voice on the other end, his life as a priest would be over. Shortly after that, he would be lying in a grave.

He hid his disease as long as he could. Each day, he seemed to grow a little weaker, a little more paranoid. There was no one who could help. Priests just didn’t get AIDs back then. If they did, they took a leave of absence and took their secret to the grave.

It tore at him that he might be infecting others. He stopped distributing Communion, but he was still handling the bread and wine every morning at Mass. That’s the way we thought of AIDs back then. You could catch it through casual contact.

Eventually, Michael became so ill, he had no choice but to step aside. He didn’t want to infect anyone and didn’t want to die alone. He'd call his bishop, tell him the whole sordid tale, and drive over to the hospital to die. Alone, as men like him deserved.

Several times he picked up the phone and dialed. Each time he stopped and hung up. Days went by. Each day he grew weaker. The phone sat on his night table, staring at him. Daring him to make the call that would end life as he’d known it. He’d be exposed as a sinner. A hypocrite. A man who deserved to die alone, in shame. The people would talk behind his back. No one would dare come to his wake or funeral.

On what he was sure would be his last day as a priest, he finally picked up the phone and dialed. The voice that came on the line was bouncy and familiar. The bishop was in a good mood. After the usual pleasantries and just enough small talk, Michael slowly laid it all out: what he’d done, what was wrong with him, what to do with his remains. Then he choked back his tears and said he was sorry.

“I’ll be right over, Mike,” the bishop said, not changing his tone. “Soon as I find my damn keys.”

Michael hung up the phone and made a pot of tea, sliced some of Sister Mary’s good Irish bread, and waited. He had to use the restroom twice, once to throw up.

The bishop was all smiles as he walked in the parish office, taking off his jacket and pausing to greet the little staff. When the chit-chat was done, he angled himself toward Michael’s little office and smiled broadly at the staff.

“I’m going to borrow Father Mike for a while,” he announced.

The bishop walked back toward the little office with a big smile, shaking out his umbrella. The rectory was a converted garage smothered with cheap, dark paneling everywhere you looked, so finding a spot for the wet umbrella was no problem. After a long moment, however, he just tossed it over into the corner.

As he backed up to make room for the bishop, the little man walked around the desk and gave him a hug. Not exactly a bear hug; they weren’t friends. But a hug is a hug. On that awful day in 1986, it was exactly what Michael needed. It was a start, anyway.

“How the hell are you, Mike?” the bishop asked, dropping his slight frame onto the edge of an armchair and waiting.

“You know,” Michael stammered, “I’m so sorry, bishop.” The words poured out from somewhere he didn’t know was there. Somewhere painful that just kept growing inside him. “I never meant to….”

“I know, Mike. Let’s you and me head over to St. Joe’s, shall we? Bill Hennessey will meet us there. You know Bill? Good man. He’ll get you checked in, check your viral load, whatever the hell that is."

"We’re gonna get through this, kid, you and me,” the bishop smiled. Then he pulled out in front of a city bus.

“We’re gonna get through this.” Those were the first words of hope he’d heard in months. They echoed in his ear as he drifted back into silence.

“See if you can find my parking pass, will you, Mike? I got the head nun here to give me a parking pass, but I can never find the damn thing.” After some more fumbling, he found the pass in his pocket and placed it conspicuously on the dashboard.

“Gotta make sure they can see it. They got some nun on a scooter, runs around giving out tickets. Attila the Nun, I call her.”

“I didn’t bring a change of clothes or anything,” Michael noted as they walked up the steps to the main entrance.

“You won’t need clothes,” the bishop smiled. “You just give them your blood, they run a few tests, and we see what they say. Here’s Hennessey,” he smiled and gave a tall, barrel-chested man a big Irish hug.

“Bill, thanks for seeing us. This is Mike,” he added, smiling and pointing. “Mike’s the man I was telling you about.”

“Well,” Bill Hennessey nodded, not shaking hands, “Let’s get you checked in and see what we’ve got, shall we? The nurse at the desk will give you all the paperwork we need.”

Michael followed Dr. Hennessey through some double doors and into a side clinic, where he motioned for him to sit down. “Make yourself as comfortable as you can. They’re gonna draw some blood, run some tests,” he nodded. Then he smiled and shook his head. “That bishop’s a character, ain’t he?”

Back then, you couldn’t get test results for days, so Michael gave them every liquid he had, then went to look for the bishop, who was munching an apple and some cheese in the corner of the waiting room.

“I thought you’d want a private room,” the bishop smiled. “I had my gall bladder out last year, they stuck me in a double room with some guy didn’t speak English and wouldn’t shut up.”

When Michael was settled in, the bishop pulled up a chair and started playing with the TV remote, which he apparently didn’t understand. “The game’s coming on,” he mumbled, pressing every button imaginable. They talked college football for the next ten minutes or so, which cheered the bishop up, since he had been a wide receiver in college. Then, all of a sudden, he launched into a long and personal story about his life.

“So now that you know almost everything about me, I want you to do me a favor. I want you to hear my confession. Might as well hear the rest of my sins, eh?” And he took out a thin purple stole, wrapped it about Michael’s neck, and launched into a recital of his sins.

Michael was stunned by the role reversal. Instead of reciting Michael’s sins, the bishop – eccentric though he was – confessed his own and asked Michael to help him find forgiveness. When they were done, Michael wrapped the same thin purple stole about the bishop’s neck and did the same. Two brother priests helping one another get through a day filled with imperfections.

When they were done, they embraced a little and wept a little and didn’t say anything for a long time. There was nothing to say. They understood one another in their imperfection. In the end, maybe that’s all any of us can do. Also, the game was coming on.

As Michael regained his composure, the bishop made a quick phone call, then turned to watch the game. He made a trip to the cafeteria, returning with the words: “All they had was macaroni and cheese. How the hell are we supposed to watch the game with just macaroni and cheese, hah?”

Michael smiled politely and sat back to watch the game, his attention wandering as the bishop gave a running commentary after every play. As they approached halftime, something amazing started to happen. One by one, some priests of the diocese began appearing in the doorway, saying something lame about making their rounds, and pulling up a chair to visit. They’d stay for a few plays or a quarter, make small talk with the bishop, then take their leave, each of them giving Michael a hug, big or small, as they left.

“Be back tomorrow, kid,” Old Tim Farrelly said with a pat on the arm. “You ain’t going through this crap alone.”

“Thanks, Tim,” Michael said. Before he could elaborate, Dick Welsh was at the door, making wisecracks about the bishop’s team, who were losing badly.

Eamon Cooney came next, with Paul Hanley right behind him. They stayed till the game was over, having dropped off the bishop’s car. A dozen or so other confreres just popped their heads in and said a few words. Pat McMullen brought Mike his breviary.

When the last of them had come and gone, the bishop came back with a briefcase, from which he extracted everything he needed to celebrate Mass. Which was exactly what they did for the next forty-five minutes, two brother priests doing what came naturally. When the time came, they gave each other Communion without batting an eye.”

“I’ll be back tomorrow, same time,” the bishop said, packing up again. “I’ll bring us a pizza. And maybe a grenade launcher for that nun on the scooter,” he smiled.

For the next two and a half months, as Michael’s body began its final journey, the bishop spent part of every afternoon in his room. Eventually, he had to feed him and help him drink through a straw. Most days, there was a more or less steady procession of their colleagues popping in and out, sometimes joining them for Mass, always for prayer.

In the end, Death came as a friend, comforting a man who expected to die alone and ashamed.

When it was over, the bishop celebrated Michael’s funeral at the cathedral, with more than a hundred of their fellow priests at the altar, each of them knowing something similar could have happened to them. Not AIDS, perhaps, but some little secret they kept hidden from the world. As Michael’s body was led back down the main aisle, they chanted the traditional Salve Regina as they had so many times before. And not one of them said an unkind word or listened to the whispers of others. He was one of them. He was a brother. That’s all they needed to know.

__________________

When I had finished my talk, I said a silent prayer, then walked back to my chair to the side of the altar. I had just given the best talk of my life, one that left the room in stunned silence.

Yet I had one question. Who in God’s name was Michael?

I had just told a story with absolute conviction and in great detail about a man I had never met. I sat there, stunned, as we finished Noon Prayer and filed out. The bishop came over to thank me. The Chancellor gave me a check for my services. It was all so – so routine.

But it wasn’t routine. I had been taken over somehow by words that weren’t my own. Words that were meant to be heard – but why and by whom?

I drove home that afternoon, feeling as if I’d been used. To this day, I don’t know how or by whom, or even why. Something more powerful than I took hold of me and gave me words to speak. Or so it seemed to me at least. They were good words. Powerful. I could see they’d had an impact on the men who sat in silence. But these words had reached them. They had touched a nerve somewhere deep inside. A man like them had asked to die with his boots on. And men like them had delivered.

They were good words. But they weren’t mine. I had an entirely different talk prepared for that day. Yet something happened and different words came out. I would spend weeks wondering whose words they’d been.

As time went on, that talk began to recede in my mind as other ideas pushed their way to the fore. I gave good talks. But the words never came back to me again. Not as they had that day. So I continued to wonder if they’d meant anything at all. And I never tried to tell the story.

Then it all changed again. On a chilly day in January, 1987, I was walking into the Chancery offices when I saw a priest reading something at the front desk where notices were posted. We chatted for a minute, then he walked off and left me standing there. For some reason, I decided to read the notice.

A young priest of that neighboring diocese had died. I immediately recognized him as one of the priests who attended my retreat a few weeks back. I knew the man. He’d been the bishop’s secretary, his Master of Ceremonies.

Suddenly, I felt there was a connection, but I didn’t know what it could be. That man was only thirty or so, I thought. Had there been an accident? So, I made a call.

There had been no accident. The young priest had become mysteriously ill and died. I had a feeling there was more to the story, but the secretary wasn’t volunteering any information. So I thanked her, hung up, and said a prayer for a promising young man cut down in the prime of his life. As happens in this life, I soon put it out of my mind.

It was only two years later that I learned the truth. I was attending a training course in New Orleans, where a friend from that neighboring diocese was on sabbatical. We met for dinner at a wonderful place on St. Charles Avenue, near the Pontchartrain Hotel in the Garden District. After a drink and some polite conversation, he mentioned the death of the young priest.

“That’s right. I heard that. What happened to him?”

“Right. Like you don’t know. You wrote the script. We followed it, the way we were supposed to. Everyone knows that.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about. What script?"

“All right,” he said, leaning over the table. “I’ll play your game. Tell me this. Tell me how you give a talk about a priest who dies of AIDs a month before one of our guys dies of AIDs. Hmm? Tell me that!” He leaned back in his chair and drummed his fingers on the table.

“He died of AIDs?” I asked. “I didn’t know. How would I know that?”

“Because the bishop told you,” he insisted. “Everyone knows that. He brought you in, told you what was going on, told you what to say, and you said it. Then voilà! The bishop’s secretary announces he’s got AIDS, and we all follow the script.

"The script you wrote,” he added, jabbing the air with a finger. “The Old Man brought you in to clean up the mess, is what happened.”

“You think my talk was a setup?” I just sat there and stared at him, incredulous.

“I can’t think of any other explanation. You really want us to believe it was all a coincidence?”

“I don’t really care what you think. I gave the talk without speaking to the bishop or anyone else. I was shocked to find out the man had died.”

“If the bishop didn’t tell you what to say, and the man didn’t tell you what he had, why did you give the talk you did?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted. I couldn’t explain what had happened because I didn’t understand it myself. “But if you like, let’s call the bishop and ask him whether he set it all up.”

“Right,” he snickered, “like he would fess up after all this. He’s gonna claim it was all a divine intervention or something.”

There wasn’t much point in continuing the conversation, so we called the waiter, paid the bill, and went our separate ways.

That was more than thirty years ago. Over time, I’ve come to terms with the fact that something or someone had worked through me to help a bishop and his priests do the right thing for a dying man. Death had come to Michael as a friend. And they were all better for it.

Nothing extraordinary. No miracles. They just did what brothers are supposed to do when one of them is hurting. Except it would have been so easy to do the opposite – to do what everyone else would have done: judge and condemn. In a sense, we all followed a script -- not mine, but one someone else had written -- and something divine had managed to shine through our humanity, and to heal what needed healing.

What is that something? It's what people have called "God" since time immemorial. And it's real.

Friar Robert: If there's a God, why is there suffering in the world?

This is perhaps the most frequent objection posed by people who have a hard time believing in God: if God is good, why does evil exist? And why would a good God cause (or allow) people to suffer?

Permit me to offer the reply I have found most helpful over the years -- one that has a sound foundation in Scripture. You can find a long presentation of this reply in a book by Rabbi Harold Kushner entitled "When Bad Things Happen to Good People." Notice that the author doesn't title his book "Why Bad Things Happen to God People." He's dealing with a prior question that takes for granted the fact that bad things do happen to good people.

We begin with a brief lesson in biblical theology. In the Hebrew bible, which Christians call the Old Testament, we encounter something scholars call "the biblical theology of retribution." In a nutshell, it means that God rewards the just and punishers sinners. If someone lives a good life, they can expect to enjoy wealth and health until a ripe old age. If someone does evil, they can expect to die young and with few possessions. So, for example, when the patriarch Isaac blesses his son, Jacob, Jacob becomes a great man, the father of the twelve tribes of Israel. In Deuteronomy 30, we read:

"See, I set before you today life and death, the blessing and the curse. If you obey the commandments of the Lord, your God, which I am giving you today, loving the Lord, your God and walking in his ways, and keeping his commandments, statutes and ordinances, you will live and grow numerous, and the Lord, your God, will bless you in the land you are entering to possess. If, however, your hearts turn away and you do not obey, but are led astray and bow down to other gods, and serve them, I tell you today that you will certainly perish; you will not have a long life on the land which you are crossing the Jordan to possess."

And therein lies the rub. Because sometimes the good die you. Sometimes the corrupt live long lives filled with everything a man could want.

The author of When Bad Things Happen to Good People, Rabbi Harold Kushner, wrote the book because he felt he had been a good man all his life, but his son was dying of a terrible disease: progeria. If you're not familiar with it, progeria causes the person to age rapidly, so that a ten-year-old might have the appearance of a 70-year-old, and most patients with progeria die in their teens.

Rabbi Kushner and his wife watched as his young son became an old man right before their eyes, then died before most teens were ready for their prom. How, they asked, could a good God allow this to happen to an innocent child? How could God allow it to happen to them? Rabbi Kushner, a man of God, searched the scriptures for an answer. But none came.

Eventually, the Rabbi concluded that the difficulty lay in our notion of a perfect God: all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good. As he studied the pages of the bible, he began to see that the God revealed there, though one who is "on our side" as much as possible, is not in control of the minutiae of our lives. God wants the best for us, but God doesn't interfere in the everyday conduct of our lives, so that evil and suffering have room to take root alongside the goodness of our God.